Tsotsi Miriam

Summary:

- Tsotsi Miriam In The Bible

- Tsotsi Miriam Quotes

- Tsotsi Miriam Smith

- Tsotsi Miriam Lee

- Tsotsi Miriam

- Tsotsi Miriam Palmer

Tsotsi, a gang member living in a township, makes a living mugging and carjacking more affluent people. One day, while hijacking a car, he finds a baby on the back seat and takes him home. Identifying with the baby, he forces a young mother in the township to take care of him. Slowly remembering his own childhood, and his mother who had died from AIDS, he ends up returning the baby to his affluent parents.

A young widow named Miriam helps Tsotsi on this journey. Throughout her involvement with the situation, she’s primarily concerned with the baby’s safety and well-being. She’s also willing to confront Tsotsi about him returning the child to his mother (“You can’t give back her legs, but you must give back her son”). Summary: Tsotsi, a gang member living in a township, makes a living mugging and carjacking more affluent people. One day, while hijacking a car, he finds a baby on the back seat and takes him home. Identifying with the baby, he forces a young mother in the township to take care of him.

Analysis:

Tsotsi Miriam In The Bible

A major success in both South Africa and around the world, winner of the 2005 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, Tsotsi took some risks: it featured no stars, but for the most part young unknown actors, was shot on location in Soweto, and its dialogue is mostly in tsotistaal, a hybrid of languages, such as Afrikaans, Sotho, Zwana and Zulu, spoken in the townships around Johannesburg. At the same time the film sparked much debate and controversy as far as its politics are concerned.

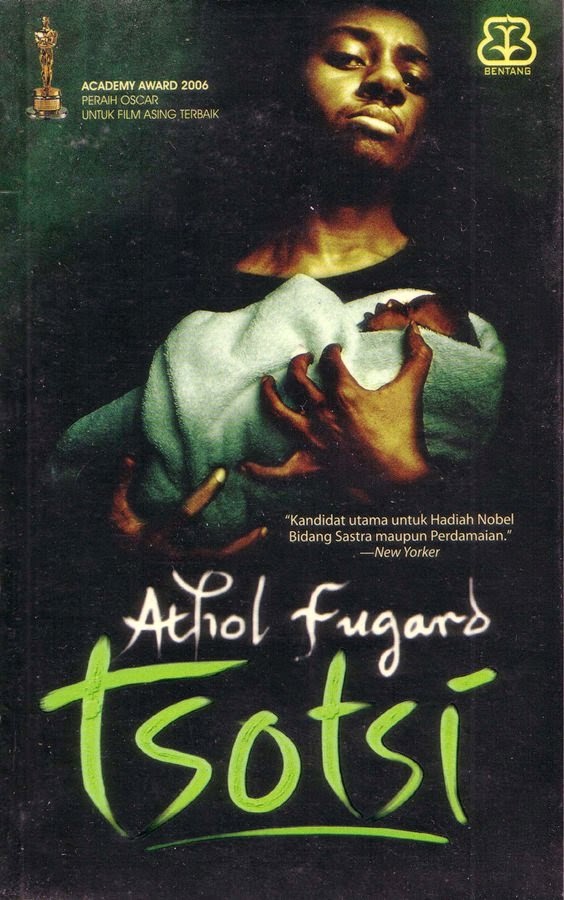

Tsotsi is based on the novel by the same name written by accomplished South African playwright Athol Fugard. Fugard had started the novel after the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, during which 69 people protesting pass laws restricting the movement of black South Africans were shot by apartheid police. Not published until 1980, four years after the Soweto uprising, during which police shot numerous students protesting the introduction of Afrikaans as the language of instruction, the novel is set in Sophiatown in the 1950s, shortly before this black cultural hub where non-whites could own property was razed to make room for the white suburb Triomf. The film updates the setting: Tsotsi’s mother does not die because of apartheid, but of AIDS, and the baby is not ‘historyless’ (Rijsdijk and Haupt 2007: 38) but has affluent black South African parents, which introduces an entirely new storyline.

Critics have thus rightfully pointed out that in the film economic apartheid has replaced racial apartheid. The affluent black father is comfortable speaking up against the police and making a claim on the State. Within such economic apartheid, the film explores different kinds of violence, domestic, criminal and systemic (Dovey 2007: 155), but does not necessarily offer possible solutions to the violence. Within this context, the film’s ending is important: Hood shot two versions, one in which Tsotsi escapes and another in which he gets shot by the police, but decided to use neither. Instead the film ends with a confrontation between the affluent black father and poor Tsotsi, leaving ‘the final critique of Tsoti’s violence to contemporary viewers’ (Dovey 2007: 160). But a pirated version with the ending in which Tsotsi is shot by the police circulated widely in South Africa, allowing for a very different reading of the film.

It may therefore not be surprising that the film has divided critics: South African critics have generally been much harsher with the film, while foreign commentators tend to defend it. Disagreements concern the film’s (un)willingness to critique the state as well as its representation of class, race and gender. Daniel Lehman, for instance, argues that the film critiques the economic and AIDS policies of then President Thabo Mbeki, who encouraged black economic empowerment for a select few but did little about widespread poverty, and who refused effective HIV treatment, which he saw as an ‘assault on … black male sexuality’ (Mark Gevisser quoted in Lehman 2011a: 97). By contrast, South African critics argue that the film legitimises the State, by having fairly sympathetic white cops, by allowing the AIDS issue to be lost in the background of the plot, and above all by insisting on Tsotsi’s positive, but entirely internal change that leaves all the responsibility up to the protagonist, apparently suggesting that individual initiative is enough and that economic, health and other state policies do not have to be changed (see Dovey 2007; Barnard 2008).

At the heart of these debates is the question of how important – or how unimportant – the film’s relatively conventional, Hollywood-style narrative is. Gavin Hood himself has said that he filmed a classic story of redemption that he thinks has universal appeal (see Archibald and Hood 2006). His camera movements, he suggests, are minimal, driven by characters (Gunn 2009: 49). In classical Hollywood stories, (usually male, white) protagonists drive the plot. In Tsotsi, Tsotsi (a word meaning thug) starts out as a nameless, expressionless character tortured by flashbacks. In the course of the story, as he identifies with the baby (whom he gives his own name), he remembers more and more of his childhood. Emotionally driven flashbacks tell his traumatising story: after his father – who, misinformed about AIDS, would not let his son near his dying mother (though he probably infected her with the virus) – kicks and paralyzes his dog, David, as he was then called, runs away, becoming a homeless child and a nameless thug. While the film tells the story about how Tsotsi, through the baby and by remembering his traumatic past, finds respect and decency, critics have pointed out that such a transformation is both unlikely and problematic. In the film, Tsotis’s maturation, or Bildung, happens all too easily. By contrast, Rita Barnard argues, the novel is a ‘meditation on the sociopolitical preconditions for a coherent subjectivity and narration’, a meditation, that is, on how the apartheid state makes telling one’s story, and thus one’s maturation and social mobility, difficult if not impossible (Barnard 2008: 549).

More specifically, Tsotsi is part of the gangster film genre. The word tsotsi, possibly derived from the English zoot suit, first emerged in 1930s Sophiatown, and represents an appropriation and transposition of the American gangster into a South African context. Not exactly unlike the American gangsters who often emerged in poor, ethnic environments, the tsotsi stands for mobility, violence, fashion – in short everything poor blacks were not allowed to be under the apartheid regime. As Rosalind Morris has it, the tsotsi ‘invest[s] the township with commodity desire’ (Morris 2010: 99). But while stylishness can sometimes be marshalled for radical politics, as it was for instance in the zoot suit riots of 1943, the connection between stylishness and critique is not always obvious. Barnard complains that ‘gangsterism purely as style … [is] not a real threat to the status quo’ (Barnard 2008: 561). Such stylishness also approaches Tsotsi to film noir, a film movement often noted for its sense of style and fashion, and in this context one could easily look in more detail at the film’s careful use of colours and lighting.

Tsotsi Miriam Quotes

But fashion and stylishness are not everything. Dovey helpfully points out that from the 1950s onward, there were two different kinds of tsotsis, ‘smartly dressed gangsters who tend to operate on big money from whites or Asians (represented in Tsotsi by Fela) … [and] marginalised boys who operate out of the desperation of poverty and who tend to serve the former kind of tsotsi’ (Dovey 2007: 154–4). Tsotsi/David belongs more clearly to the latter kind, and in this context, it would be interesting to think of another of Hood’s stylistic choices: his widescreen images place faces in landscapes, emphasising how much Tsotsi/ David belongs to the township, as well as the gulf that separates the township from the modern city. Tsotsi/David remains embedded in the landscape, unable to escape the township (Dovey 2007: 154).

No discussion of Tsotsi would be complete without a discussion of its soundtrack. Many have noted the marked presence of kwaito music by South African artist Zola who also plays Fela in the film. Many of these tracks were pre-existing hits, and Zola’s celebrity was used to market the film and its music (Rijsdijk and Haupt 2007: 33). Kwaito was first developed by gangsters in 1950s Sophiatown, and has been influenced by gangsta rap. Ian-Malcolm Rijsdijk and Adam Haupt have argued that the use of Zola’s kwaito music ‘constantly re-affirms a homogeneous black urban masculinity by not offering musical diversity’ (Rijsdijk and Haupt 2007: 36). But kwaito is not the only music in the film, there are also ‘choral arrangements, and … the combination of low bass notes, rattles and percussion that accompany scenes of action or tension in the film’ (Rijsdijk and Haupt, 2007: 31). In the course of the film, we see a shift from the ‘urban, fast-paced, heterosexist, aggressive and lyrically violent music of Zola to the soulful choral style of Mahlasela and Maphumulo’ (Rijsdijs and Haupt 2007: 31). Tsotsi/David’s emotional transformation gets associated with choral themes.

As becomes evident in this discussion of the film’s music, questions of gender have lurked everywhere in the critical debate surrounding Tsotsi. Rijsdijk and Haupt conclude that the film runs the risk of ‘essentialising conventional gender roles in which women are nurturers and men are violent plunderers’ (Rijsdijk and Haupt 2007: 41). As noted earlier, the upper-middle-class couple is an addition in the film; in the novel, Tsotsi does not hijack a car but encounters a frightened, black woman in a grove and comes close to raping her. The topic of rape has disappeared from the film, although, Dovey reminds us, there was a 400 per cent increase in child rape in South Africa from 1988 to 2003, and that in 2003 children under 12 made up 40 per cent of South Africa’s annual 1 million rape victims, in part because of the myth that raping a virgin would cure HIV/AIDS (Dovey 2007: 157). By contrast, Lehman focuses on the character of Miriam who takes on ‘an increasingly proactive function’, whose encounters with Tsotsi suggest that Hood does not avoid the topic of potential sexual violence (Lehman 2011b: 118). Along with the baby, she nudges Tsotsi toward a less aggressive masculinity, an alternative to the masculine violence also embodied by his father. Not coincidentally, when the film came out, real tsotis objected that Tsotis/David looked too soft and sloppy (Dovey 2007: 153).

Tsotsi can be located in the context of the postapartheid flourishing of South African films, which often have high production values and run the risk of being ‘Hollywoodised’. The NFVF (National Film and Video Foundation) specifically allocates funding to films that are adaptations of South African literature, which tends to privilege texts by white South Africans. Likewise, white directors have been more enamoured by the themes of reconciliation and redemptions than black or coloured directors. At the same time, Tsotsi also participates in a wave of internationally acclaimed films about gangsters and hoods, including the Brazilian film, City of God (2002) and the AngloIndian film, Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Like these other films, Tsotsi toys with the tradition of neorealism, famous from films such as Bicycle Thieves (1948), which employed non-professional actors, yet, at the same time, the film’s production values and narrative resemble Hollywood melodrama. These different legacies certainly help explain some of the contradictions of the film, which have generated so much debate.

Sabine Haenni

Cast & Crew:

[Country: South Africa, UK. Production Company: The UK Film and TV Production Company PLC, Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa, The National Film and Video Foundation of SA, Moviworld. Director: Gavin Hood. Producer: Peter Fudakowski. Screenwriter: Gavin Hood (based on the novel by Athol Fugard). Cinematographer: Lance Gewer. Music: Paul Hepker, Mark Kilian. Editor: Megan Gill. Cast: Presley Chweneyagae (Tsotsi), Terry Pheto (Miriam), Kenneth Nkosi (Aap), Mothusi Magano (Boston), Zenzo Ngqobe (Butcher), Zola (Fela), Rapulana Seiphemo (John Dube), Nambitha Mpumlwana (Pumla Dube), Ian Roberts (Captain Smit), Jerry Mofokeng (Morris).]

Further Reading

David Archibald and Gavin Hood, ‘Violence and Redemption: An Interview with Gavin Hood’, Cineaste, Vol. 31, No. 2, Spring 2006, pp. 44–47.

Rita Barnard, ‘Tsotsis: On Law, the Outlaw, and the Postcolonial State’, Contemporary Literature, Vol. 49, No. 4, Winter 2008, pp. 541–72.

Lindiwe Dovey, ‘Redeeming Features: From “Tsotsi” (1980) to “Tsotsi” (2006)’, in Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2, December 2007, pp. 143–64.

Judith Gunn, Studying Tsotsi, Leighton Buzzard, Auteur, 2009.

Daniel W. Lehman, ‘Tsotsi Transformed: Retooling Athol Fugard for the Thabo Mbeki Era’, in Research in African Literatures, Vol. 42, No. 1, Spring 2011a, pp. 87–101.

Daniel W. Lehman, ‘When We Remembered Zion: The Oscar, the Tsotsi, and the Contender’, English in Africa, Vol. 38, No. 3, October 2011b, pp. 113–29.

Rosalind C. Morris, ‘Style, Tsotsi-Style, and Tsotistaal: The Histories, Aesthetics and Politics of a South African Figure’, Social Text, Vol. 28, No. 2, Summer 2010, pp. 85–112.

Ian-Malcolm Rijsdijk and Adam Haupt, ‘Redemption to a kwaito beat: Gavin Hood’s Tsotsi’, in Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2007, pp. 29–46.

Source Credits:

The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films, Edited by Sarah Barrow, Sabine Haenni and John White, first published in 2015.

Tsotsi is an African film that shows the contrasts between the rich and poor divide (Binary Opposition) and tells a story in the eyes of a thug and shows redemption and even a thug can change. Which is in the title. Tsotsi is translated into thug in english. This shows that not every thug is a thug all the way through him and even as something small or vulnerable as a baby can change even the hardest of thugs life around. The genre of this film in my opinion is a Crime Drama.

Narrative- A thug from Johannesburg is in a gang and causing trouble throughout the town he is in. When he is on one of his jobs in the rich side of the town he comes into contact with a baby that will change his life around. As the film goes on he cares more and more for this baby and he changes his life around and become less of a thug. You see the horrid life he lived at a young age that got him to this point and see the journey he has been on and will take. Only one person sees so much more than he lets on to be (Miriam) and those emotions come out more and more as the film goes on.

The Codes and Conventions of any film is basically the unwritten rules for the colours and lighting for that genre of film. For example if it is a comedy film then the colours will be bright and the lighting will be bright to make a happy emotion for the audience. If it is raining in a comedy film then the audience will suddenly feel down and not find it funny just because what is on screen. For Tsotsi as this is a Action, Drama the colours are dark and pure. It depends what is happening on screen. When Tsotsi is being a thug and hitting people or talking about bad things like when a flashback happens and he thinks about his father and his mother and how his father killed his dog and he ran away and thats how he become homeless its at night. So the colours are very dark and its raining which is a sign of emotion being poured out in the character even if they don’t show it. Its more than likely to show that they are upset or crying. When the audience see’s rain on the screen it changes their emotion as-well so the audience can empathize with the characters on screen. As we are looking through the eyes of the ‘thug’ then we empathize with him as we can see through his eyes but if there was another main character in the film and we didn’t follow his story we would look at him as a bad guy.

When the baby comes into view and the rich side of Africa, then the colours become pure. This is the point in the film that he changes his life. There is a point in the film when Tsotsi tries to stop the baby crying by putting on some music and dancing because he doesn’t know what to do. At first when he brings the baby back to the shanty town and in his shack then its just dark but as he goes along and continues looking after this baby sun shines through the shack and onto him. This could mean that his soul is becoming more pure with the help of this baby and now he has to look after someone else and not him-self for a change.

Already through this film at the beginning of the film the first shot you see is Tsotsi doing a stabbing on a train for money. So the audience reaction is not vert sympathetic towards this character only the character who got stabbed. The clothes he is wearing are very dark with browns and blacks and also leather. These are the clothes and the colors of bad people who commit crimes, you will see throughout the film the changing of clothes is different and more free. By the end of the film his clothes change from dark colors and leather jackets to a white loose shirt and black trousers. White symbolizes pure, church and freedom, with the help of the baby he is a changed person. The contrast from Tsotsi at the beginning from Tsotsi at the end is so different. If the he stayed the same person throughout the film then the film will be changed and he would continue being violent and he would keep on running away form the law. If that baby wasn’t in that film then you wouldn’t of had that story and nothing would of become of him. Baby’s are normally seen; in the eyes of people, immature, vulnerable, not a person yet, can’t cope on their own and they learn from adults. If you change that around, you could describe Tsotsi with the same exact words. But the difference is that he learns from the baby and not the other way round. He is not learning like everybody else does, with looking after this baby, he is learning responsibility and he is now getting feelings towards it. He looks up to this baby like a guru if you like to call it that. He teaches him life lessons without him knowing it.

The genre is Crime Drama. The reason it is Crime Drama because in the beginning you know Tsotsi as a thug, he stabs somebody on a train for money, he steals from a homeless guy in a wheel chair and there is aspects of crime in this film but there is also aspects of Drama in this film as-well like the flashback within the film when he looks back at his Family and the reason why he ran away and become the guy that he has become and that change in his life.

Tsotsi Miriam Smith

In the crime genre the structure is, there is a murder, then and investigation then it is solved. Within this film, there is a murder and there are knives and guns involved which you would link to the crime genre. There is the good cop and the bad cop and they try to find Tsotsi and how Tsotsi lives is with guns and knives. That is how this can be within the crime genre.

The Drama genre, normally tells you the story about family struggles. Which this does tell you when he goes back into his flashback from how his mother died form how his father treated him and why he ran away and how he ended up in the end. You can also class him changing with the baby in his life is a struggle for him to change his life and he cares for that baby and he didn’t think that he could care for anybody. The first time you see this emotion is when he follows the homeless guy in the wheel chair and starts harassing him. He reminds him of his dog that he had and become ‘crippled’ is how he described him as his dad hurt the dog and the guy couldn’t walk. This is the first emotion that you see from him.

In this film i think there are more elements of the Drama genre then the crime genre because this film is all about redemption and how his life changes and at the very end if he continued because the thug he was he would of ran away from the police and show no emotion but he changed. His clothes changed from being leather and dark to at the very end just a white loose shirt. That is the color of purity. He doesn’t want to give away the baby and shows emotion because he got attached. You could say here that he couldn’t changed without help and now it was time to let go he wasn’t ready. You can also say that as the baby was form the rich side of the country that the poor just need help from that side even if they just care and they will be come better people.

Tsotsi Miriam Lee

This film is all about the rich and poor divide and how people want to change. There is a scene that stands out to me when he first has the baby and he sees a single mother with her baby and he goes to her to feed his baby. But he holds her to gun point while she breast feeds. For a living she makes chimes and sells them. Tsotsi goes up to them. There is one which is old and rusty and right next to it is one very colourful and inviting and bright. He looks straight thorugh the old rusty one and touches the colourful one with his gun. Here is could represent him. The person he is and the person he will be. A gun shows power and security. As he just looks straight through the rusty one it could show that he is invisible and wants to move away from it and break away. But while looking up the the colourful chime and touching it with his gun this could shows he looks up to people like that but scared to step in that direction. You could say here, he is in limbo. Too scared to move forward but doesn’t want to take a step back.

Representation within this film is Race, Gender and disability. For race, as this film is a African film and the director is not african it shows it through the eyes of a different person. It shows two different parts of the country and what they go through in Johannesburg. Here they are seen as dangerous as Johannesburg has one of the highest crime rates ad as the main character is a thug then it points the audience in that direction. Through gender the male characters are the strongest physically but the females are stronger through mind. So it kind of equals itself out. With the disability is with the guy in the wheel chair. As he is a homeless person it kinds of shows him as weak and cant look after him self and he is vulnerable and a easy victim. In the train station people just walk right by him and not even bother with him. When they do bother with him he is being a target.

Theories- The film doesn’t just go by one theory i think it combines. With the Aristotle theory there is just a beginning middle and end. But i think think this film is more complex than 3 stages within the film. Levi Strauss theory is Binary opposition, this has defiantly got binary opposition between the rich and poor divide. Yladmir Propp theory is 8 types of characters. The hero, villian, donor, dispatcher (messenger) false hero, helper, princess and her father. I don’t think some of these apply but some do like the hero, villain, helper and the princess. The hero would be Tsotsi the villain would be the police, the helper or helpers would be his friends (Gang) and Miriam would be the princess. Izetan Todorov theory is 5 stages within the narrative.

1. A state of equlibrium at the outset- Tsotsi being the thug and does what he does best and commits crimes in his gang.

2. Adisruption of the equlibrium by some action- He hits one of his gang members and his gang falls apart.

3. A recongition that there has been a disruption- The baby comes along while he is steeling the car.

4. An attempt to repair the disruption- He tries to look after the baby but cant so he asked for help from the princess.

5. A vein statement of the equilibrium- The very end when he has changed and become a different person.

Tsotsi Miriam

Tsotsi Miriam Palmer

So i think the 3 theories make up this film and it just doesn’t go by one theory.

In this film you go on a journey with one particular person with a troubled childhood and the ability to change. The catch is that the change in his life was a baby. When he comes into contact with the baby he debates whether or not to give the baby back but as he is getting chased by cops he is forced to keep the baby in his apartment. He is torn between his old life and the new one that is about to come upon him. This film has so many emotional impact on you when you watch it. It doesn’t mean you will cry but you will feel different once you have seen it. When i watched it for the first time the ending got me and thats when i got the emotional impact. In other films you watch the gangster/ thug is the bad person, this film changed your perception of that character. When you see the life of someone that you think is evil it changed your way of thinking about them. The saying applies here ‘Don’t judge a person unless you walk a mile in their shoes.’ With the soundtrack in this film combines very well with the emotion shown on screen. There is a reason why this is one of my favorite films. You have to watch this film to actually know what impact it throws on you. It is not an easy going film to watch.

Structuralism is how a story goes. Its like the structure of the film, its what makes the film up. If you take away a part in the film it changes the whole film all together. The main part of the film is how Tsotsi looks after the baby, but what will happen if you took away the baby? This film will not be what it is. There will be no redemption, no change in his character and the whole story line will be different. I think it will just be a film about a thug and his life. I think it will be still a drama because of what happened in the past to him with his mother dying of aids and his father being a drunk and him running away from home. But without the baby we will not see the other side of him and he wont change.